in our couples' book group.

This introduced us once again to the personality of Aldus Manutius ...... with a new and more exciting energy. This coincidence was further augmented by our extended connection to the Bogliasco Foundation. Each year, there is an early spring gathering for former fellows at the Grolier Club in New York. In attending the last two years, we were made aware that the book collection at the Club included notable examples of Aldus Manutius publications.

The Grolier Club on East 60th Street is the country's oldest "bibliophile society," home to more than 100,000 volumes on the art and history of publishing. In 2015, before our connection with the Foundation, there was an exhibit of the work of Aldus Manutius, the 16th century Venetian printer. “Aldus Manutius: A Legacy More Lasting Than Bronze" feat ured more than 130 books published by the Aldine Press, mostly from private collections and not previously exhibited.

We became fascinated with his work, most specifically with a book entitled " I Quattro Primi Libri de Architettura" by Pietro Cataneo Senese… Venice: The Sons of Aldus, 1554.

Pietro di Giacomo Cataneo (c. 1510 - c. 1574) authored this, the only architectural book printed by the Aldine Press. The four books include over fifty woodcut images, and cover topics such as urban planning, building materials, ecclesiastical architecture, and the design of private residences. Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) cites Cataneo and this Aldine edition as an influence on his own architectural work by him. At this point we diverge at bit, rewinding the narrative back more than 40 years to our first trip to Venice. It was 1976 and 1977 when we were in Italy for a year under the sponsorship of a Fulbright Research Fellowship. We first arrived in Venice for a long weekend in October, but returned for a three month stay from Christmas through Easter.

A quick explanation may help here. My Fulbright study was associated with an investigation of Italian Rationalist Architecture in Northern Italy between the Two World Wars . For a variety of reasons I was particularly drawn to some of the more prolific practitioners in this movement. Upon arriving in Italy, and specifically in Venice, we were both 'romantically swept away' by the power of place and history that was embedded in the fabric of Venice and the Veneto. I rethought my research focus and shifted to a study of the design of the church facades of Andrea Palladio in Venice, in particular the layered elevations of his famous work, the 16th-century Benedictine church of San Giorgio Maggiore, located in the Venetian Lagoon on the island of the same name.

A quick explanation may help here. My Fulbright study was associated with an investigation of Italian Rationalist Architecture in Northern Italy between the Two World Wars . For a variety of reasons I was particularly drawn to some of the more prolific practitioners in this movement. Upon arriving in Italy, and specifically in Venice, we were both 'romantically swept away' by the power of place and history that was embedded in the fabric of Venice and the Veneto. I rethought my research focus and shifted to a study of the design of the church facades of Andrea Palladio in Venice, in particular the layered elevations of his famous work, the 16th-century Benedictine church of San Giorgio Maggiore, located in the Venetian Lagoon on the island of the same name.

Return to 2019-20 (now 2022!). The Fulbright experience and our 3 months in Venice have never drifted too far into the background, although the years have certainly passed! The stimulus of the Bogliasco connections and our exposure to the character of Aldus Manutius have had an direct influence on the research topic of my current residency at the Vittore Branca Center. My proposal is to research and write about the theme of "Comparative Duality; Space and Illusion in the Late Venetian Renaissance". While this topic is somewhat more expansive than the Cataneo reference noted above, the consideration of two and three-dimensional representation of space is central to this theme. The overlay of the Manutius compositional inventions and graphic innovations may become central to my thesis.Finally, a key to this study reaches back to my fascination with Palladio's interpenetrating Greek and Roman compositional strategies in San Giorgio Maggiore. To have the opportunity to stay in the scholar's residences on the island of San Giorgio ...... where Palladio lived for almost 20 years ...... is still hard to fully comprehend.

This is a situation, written in advance of the experience, where we are open to the suggestions that emerge in the research. The fictional narrative of Mr. Penumbra's bookstore experience has kindled a strange fantasy which we are looking forward to exploring.

For more information, we have include a bit more information on our 'colleague' Aldus below. Note the reference to Vittore Branca .....

Venice as a center of print culture

For centuries, Venice served as one of Europe's main cultural and commercial centers and as the most important intermediary between Europe and the East. The city's political stability and wealth, combined with its extensive international relationships and rich cultural and artistic life, proved to be fertile ground for the establishment of the printing press. In the second half of the fifteenth century, when printed books gradually began to substitute for handwritten manuscripts, Venice was the European capital of the printing press.

For centuries, Venice served as one of Europe's main cultural and commercial centers and as the most important intermediary between Europe and the East. The city's political stability and wealth, combined with its extensive international relationships and rich cultural and artistic life, proved to be fertile ground for the establishment of the printing press. In the second half of the fifteenth century, when printed books gradually began to substitute for handwritten manuscripts, Venice was the European capital of the printing press.

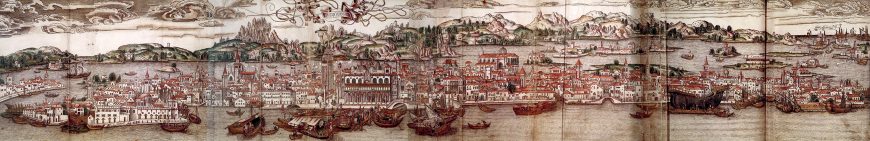

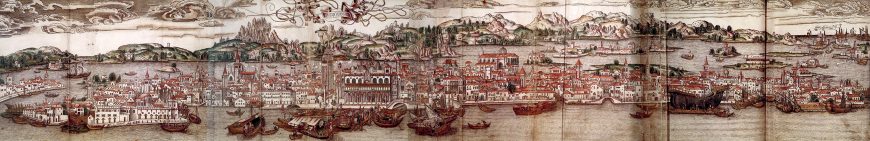

Map of Venice, 1486, from Bernhard of Breidenbach, Sanctae peregrinationes , printed in Mainz by Erhard Reuwich ( Bibliothèque nationale de France )

The invention of movable type in Germany in the mid-1400s ushered in a sea change, placing Venice on a par with modern-day Silicon Valley. Both of these creative environments resulted from a powerful combination of invention, technology and economic power.

According to the scholar Vittore Branca , at the end of the fifteenth century, an estimated 150 typographers operated in Venice, far more than the 50 or so that were active in Paris at that time. In the last five years of the century, Branca estimates that one-third of the volumes printed in the world originated from Venice.

Plate showing the operation of a printing press, from Chants royaux sur la Conception, couronnés au puy de Rouen de 1519 à 1528 , 16th century (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

Unsurprisingly, this flourishing industry generated wealth, cultural interest, and the diffusion of a new trend known as “bibliomania” —defined as a passionate enthusiasm for collecting and owning books. Readers and collectors from all over the world sought out the books of Venetian printers, who skillfully adapted production to demand. These printers created an inventory that was extraordinary in its variety, thanks also to the freedom of press granted by the government. It was in Venice that the first printed edition of the Koran was published, along with the first printed Talmud.

Books, booksellers, and bookstores

Anyone strolling through the bustling streets of Venice in the late 15th century would encounter bookstores whose windows displayed beautiful book frontispieces while catalogs of the books available either hung from the jamb of the door, or were available inside, on the counter. It was common practice for the bookseller to offer the loose pages of a book in a package which the buyer would subsequently arrange to have bound in accordance with his or her di lei taste and financial means di lei.

Bookstores soon became places where scholars, intellectuals, collectors, and book lovers gathered to discuss new editions, exchange information, and converse with the bookseller who often was also the publisher and the printer. The invention of movable type spawned an industry that led to the creation of a new professional figure, the printer-publisher, and a new business, the publishing house. The publishing house developed its own structure, investors, and also required legal advisors, due to the emergence of copyright issues.

Portrait of Aldus Manutius , nd, print, 105 x 81 mm ( Deutsches Buch- und Schriftmuseum, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Leipzig )

Aldus Manutius

“Venice is a place that is more similar to the rest of the world than to a city,” Aldus Manutius wrote in a preface to one of his books. He arrived in Venice in 1490, driven by his profession di lui as a Greek and Latin tutor. Manutius was a humanist from a small town in central Italy, and it was probably his interest di lui in him in books that brought him closer to the world of the printing press.

Manutius was one of the first publishers in a modern sense. In a short time, he transformed the concept of the book in Europe thanks to his typographical innovations di lui and to his unique editorial vision of him. He did this by founding and overseeing the Aldine Press, with the help of technicians, scholars, investors, as well as with political support. Aldine Press books were marked by a famous emblem depicting an anchor and dolphin and were known throughout the world for their accuracy, beauty, the superior quality of the materials employed, and their cutting-edge design.

The inventor of the modern book

Many of the elements that Manutius introduced, or eliminated, in the conception of his editions are innovations that have become embedded in today's books. Notably, he gave a new look to the printed page: the pages of Manutius's books featured harmonic proportions between the size of the fonts, the printed section, and the white border, according to precise mathematical principles - reflecting a major theme in Renaissance culture.

Manutius also introduced page numbers and made reading more fluid by clarifying the disorganized punctuation that prevailed at the time. He added a period at the end of the sentence and was among the first to adopt the use of the comma, apostrophe, accent, and semicolon in the ways they continue to be used today. In order to recreate the familiar effect of handwriting, he also invented what is now known in English as the “italic font,” named after it's Italian provenance.

One of Manutius's most striking inventions was the printing of small-format books, the ancestors of our modern pocket-sized publications. Small religious volumes were already in circulation, but Manutius's revolutionary idea was to publish both classics and modern works in the small format.

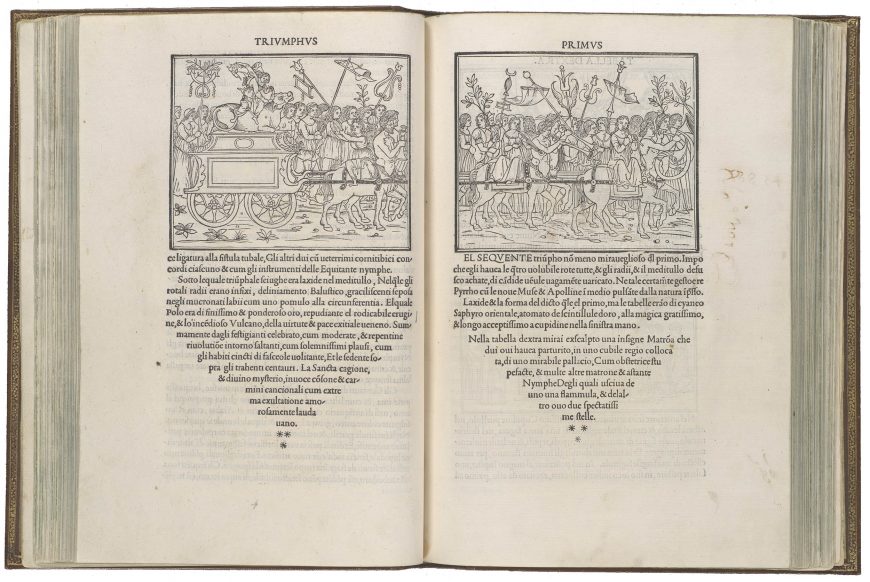

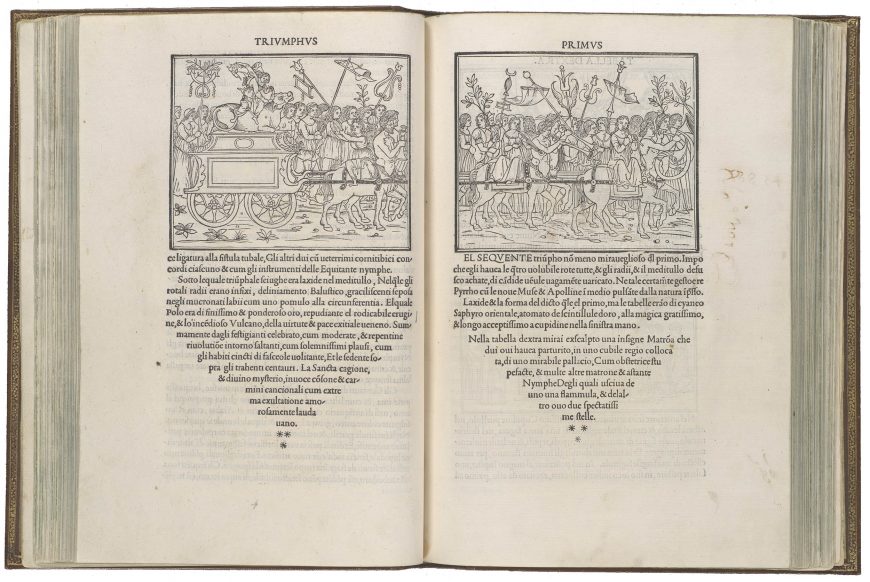

Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, published by Aldo Manuzio, 1499, book with woodcut illustrations, 29.5 × 22 × 4 cm ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art )

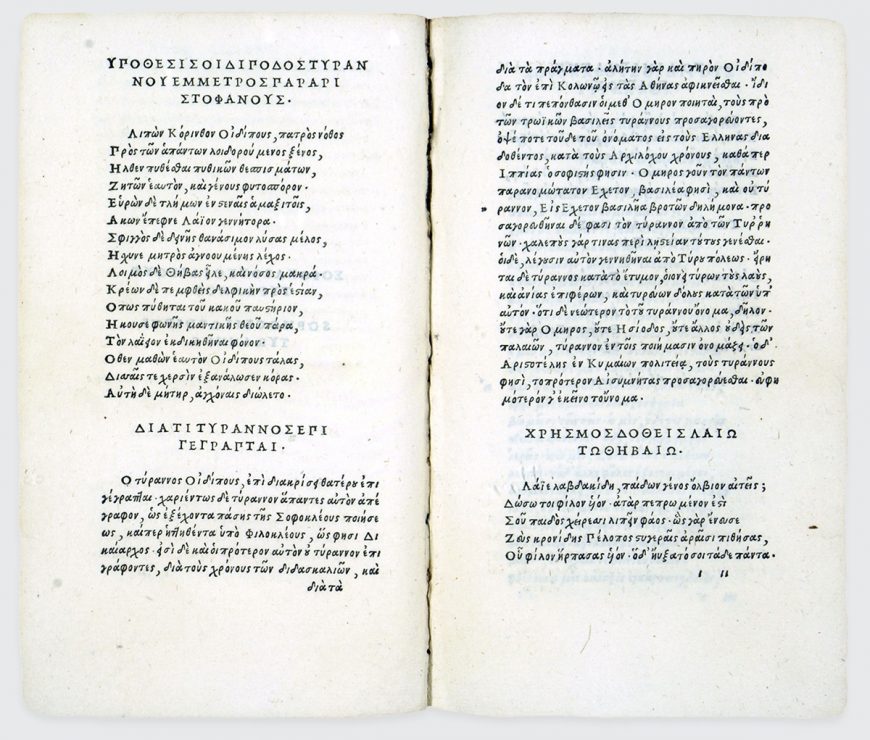

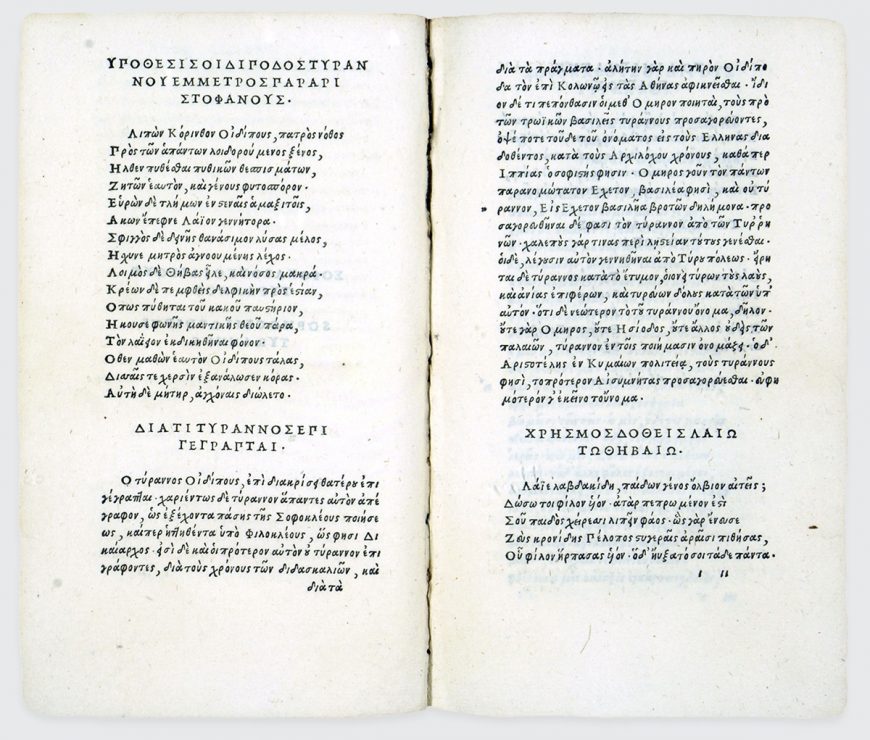

Sophocles, Tragaediae septem cum commentariis , 1502, published by Aldo Manuzio (University Library of Bologna).

It can be argued that through this innovation Manutius also invented a new audience. With pocket-sized books, reading became an intimate moment, an activity that could be enjoyed while traveling, lying in bed, or sitting on a garden bench. For the first time, the book became a manageable, easy to carry, and relatively inexpensive object, therefore it became accessible to a larger audience comprised not only of scholars, but also of aristocrats and members of the upper middle class. The small books immediately became very fashionable and conferred a certain status, as we can see in many portraits of the time.

No comments:

Post a Comment